12 Popular Games Adapted for Children with Autism

Play is often described as the “work” of childhood, where children can make friendships, learn social skills, come to understand expected group behavior, consequences, turn taking, and cooperation, not to mention have some fun! Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can reap these same benefits by playing games with other kids, though many do not naturally gain the aforementioned skills simply by being exposed to games or other play objects, as might their non-disabled peers. As with many concepts, games and their component skills may need to be explicitly taught, supported, and adaptations made in order for a child with autism to experience success with the activity.

General Guidelines for Adapting Games for Children with Autism

While the type of adaptations used for a game will depend on the child’s individual needs and the game being played, some general guidelines may be applied to ensure a successful outcome with any social play situation.

- It is wise to prepare the child as much as possible for what they will experience in a game.

- The child should have a clear understanding of what they are being asked to do before beginning the game.

- The child needs to have an opportunity to express any anxieties or ask questions (to the best of their ability) ahead of time.

- The child should have opportunities for skill practice and understand the objective of the game before beginning game play with peers.

The following is a list of popular children’s games and adaptations that can be made to support children with autism to successfully play them. It should be noted that due to the wide range of traits with which children with ASD may present, these adaptations would not be appropriate for every child. Rather, these ideas may be used as starting points or ideas for parents and teachers alike that can be used to support children with ASD based on their individual needs and abilities.

Games and Adaptations for Children with Autism

PHYSICAL GAMES

- Tag

Unlike board games or card games, which often require players to talk to one another throughout the game, physical games like tag can work well for children with ASD because there aren’t a lot of social interactions. However, the idea of being “it” can be a little abstract and children need to understand the objective and rules of the game, such as how to tag someone else, and staying within a certain area, in order to keep everyone safe. To make sure tag is enjoyable for all students, the following adaptations can be made:

Adaptations for Tag:

- Playing tag inside a gymnasium or other enclosed space may be wise for children with autism who are known to run away.

- If playing outside, preview the physical area in which the game will be played with the child ahead of time so they understand where the boundaries are.

- Create a social story or visual aid to teach the rules of tag, including the idea of being “it”, and how the person who is “it” can change (for example, “There is one person who is it, that is the tagger”; “The person who is it wants to tag, or lightly touch, another player to make them it”; “If someone else tags you, you are it”).

- Have the person who is “it” wear a special hat or some other visual marker so that everyone is clear on who is “it” at any given time as this can change often and quickly.

- If necessary, provide scripted language or a communication board for the child to use to ask to join a game of tag or let someone know that they would rather not play.

- Hide and Seek

This timeless children’s game may be difficult for children with autism who like to run or hide as it can appear to encourage those potentially dangerous activities. However, because of the limited social interactions and gross motor skills used, it can be a good choice for kids with ASD. The following adaptations may be helpful for playing hide and seek:

Adaptations for Hide and Seek:

- If the child is apt to run away, play the game in an enclosed area such as inside a house or in a fenced-in area. Care should be taken to ensure all children are aware of any boundaries that they need to stay within, both for safety and so all players know where they can and cannot hide.

- Similarly, previewing the area for potential hiding places may also be beneficial. Pointing out places that are not safe to hide, such as a refrigerator, freezer, washer, dryer, oven, up a tree, in a drainage ditch, etc., might also be important for some children.

- Provide the child with a social story or other visual support so they know what the sequence of events is throughout the game. For example, “You count to 15, I hide quietly, you look for me, and you find me. Then we switch.”

- Waiting to be found may be difficult, so giving the child something to do while they wait, such as putty to squeeze, a favorite book to look at, or quiet toy to play with, may help.

- Create a communication board or visual support to provide language models throughout the game. This may include numbers for counting and phrases such as, “You found me!” “I found you!” or “Come out, come out, wherever you are!”

- Depending on the child, these skills may be best practiced in therapy sessions or 1:1 with an adult before having the child play with peers to ensure their safety.

- Basketball

Many children with autism have sensitivities to sound and other sensory inputs. Basketball, which is often played in a potentially loud or echo-prone gymnasium, naturally has many loud noises such as the bouncing of the ball, a referee’s whistle blowing, shoes squeaking on the floor, or other players yelling at one another that can cause stress and/or anxiety in a child with autism. While adjusting the volume of sound in a gymnasium may not be feasible, there are a few options for helping a child with ASD to be more comfortable in the environment.

Adaptations for Basketball:

- Use headphones or other noise-reducing device. This can filter out much of the extraneous sound that accompanies a basketball game while still allowing the child to hear others who are talking to him/her, or sounds such as a whistle or timer that would indicate a change in action on the court.

- Discuss ahead of time, that is, well in advance of a game, practice, gym class, or recess, when a particularly loud noise may be expected. For example, talking about how people will likely cheer or yell if a basket is made can potentially help the child to better regulate his/her response when this happens during a game. Explicitly teaching that the ball going through the hoop will result in loud noises can give the child a concrete cue to look for (ball in hoop) that may help them to anticipate when some loud noises may occur.

- Hopscotch

Hopscotch is a surprisingly complex game that supports children’s physical coordination, balance, and cognitive development. From working on midline development (hopping on one foot), body control (not stepping on the lines), muscle strength (leaping over the marker), to hand eye coordination (tossing the marker), and fine motor control (picking up the marker), this seemingly simple game can have a lot of benefits! However, these very skills can be challenging, and thus potentially frustrating, for some children with autism, and may dissuade them from playing. Adapting the game can help the frustration level and provide opportunities for social interactions and turn taking with peers.

Adaptations for Hopscotch:

- Instead of just numbering the spaces on the board, use colors to differentiate them as well. This can act as another visual cue for discriminating between the different squares on the board and helping children know where to place their feet.

- Focus on one skill at a time. For example, a child might practice tossing the marker in a square and picking it up again, walking to the appropriate square rather than hopping. Or if the child is practicing hopping, perhaps they don’t need to worry about hopping over the marker or staying in the lines; rather they just hop down and back. Still other children may simply be working on taking turns and will focus on waiting until their peers are done before they begin to play on the board.

- The board can be used to reinforce other skills, such as number, color, or letter recognition by asking children to jump to the appropriate box as called out by a teacher or parent.

- Simon Says

Many children with ASD thrive with predictability and knowing what to expect. In this way Simon Says, in which one player is designated “Simon” and stands in front of the group, directing the others to perform various actions, may be challenging because no one except Simon knows what activity will be called out next. The apprehension a child may feel about not knowing what is coming next may prohibit him/her from paying attention to the language being used, (“Simon says jump” versus “Jump”,) and cause the child to be “out” before they truly have a chance to be successful.

Adaptations for Simon Says:

- Limit the activities Simon can select, such as by giving Simon a list of actions from which to choose, and providing a visual aid to the child with autism listing these same actions. The actions could be provided in the order in which they will be used in the game, allowing the child with ASD to know exactly which movement will be coming next, or as a small list from which Simon can choose, narrowing down the options and giving the child with ASD (who has the same list) a better idea of what’s to come, even if they don’t know exactly what Simon will say.

- Don’t use the “Simon says” rule (i.e., if Simon doesn’t say “Simon Says” and you do the action, you’re out) at all, and focus only the actions being performed. This removes the pressure of getting “out” and could be used as a means to practice desired behaviors such as sitting down, putting on a coat, waving, saying good morning, etc.

BOARD GAMES

As with many children’s board games, Candy Land is a fairly simple game to play, but there are sub-skills that may prohibit children with disabilities such as autism from being successful at playing it without explicit instruction. For example, it may be difficult for a child to remember his/her color game piece, how to follow the path from beginning to end, how to take turns, or how to understand when to move forward or backward on the board. Without these skills in place, game play with peers is likely to be frustrating for all involved. While these sub-skills are found in many games, some adaptations specific to how they might pertain to Candy Land are listed below:

Candy Land Adaptations

- To minimize confusion as to which game marker each child is using, attach a small photo of each student to his/her marker. Similarly, the child could also wear a paper wristband of the same color as his/her game piece to remind him/her which marker is his/hers.

- To familiarize the child with the path of the game, practice driving a toy car around the “maze” or put arrow stickers or post-it notes with arrows around the board to indicate directionality. Care should be taken to explain the “Shortcuts” (Mountain Pass and Rainbow Trail) so children understand when these paths would be taken and where they lead.

- Keep track of whose turn it is by passing something physical around the table each time it is the next player’s turn. For example, a hat or necklace could be passed around and worn during each player’s turn, or a cup placed in front of each player and passed on.

- After basic skills have been mastered, address “free move forward” and “penalty moves backwards” concepts.

Chutes and Ladders is played on a very busy game board that can be confusing to look at. Keeping track of the direction in which to move game pieces, as well as understanding when to move “up” a ladder or go “down” a chute on the two-dimensional board can make for a frustrating game-play experience. Children in general may also struggle with the fact that this game is won and lost by chance, depending on the use of a spinner and the chutes and ladders that are landed on throughout the game. Children with autism in particular may struggle with knowing what to say to deal with feelings of frustration or anger throughout the game if they are not winning or in the lead. In order to make it easier to understand the visual stimuli within the game and focus on appropriate language to use with peers, the following adaptations may be helpful:

Chutes and Ladders Adaptations:

- Define the word “chute”! This is probably not a familiar word to young children and using the word “slide” may make more sense to them.

- Before the game begins, look at the board with the child with autism, pointing out where the chutes and ladders begin and end. Tracing the path of each with a finger may help make this more concrete. Putting arrow stickers or sticky notes on the board, such as green arrows going “up” a ladder or red arrows going “down”, a slide may also help keep things straight during game play.

- Provide a script for language to be used during the game. Phrases such as, “I hope I get a ladder!” or, “Oh no, I landed on a slide!” may help the child process their own path through the game. Phrases such as, “That’s a long ladder, good job”, or “Oops, you got a slide”, may help the child know what to say to peers.

Hi-Ho Cherry-O encourages players to work on their counting skills, including basic addition and subtraction, in order to fill their buckets with 10 cherries from their cherry tree. The game is played with a spinner and taking cherries off or putting them back on the tree as specified by the spinner. To aid children with autism in keeping track of the rules and encouraging language use, the following adaptations can be made:

Adaptations for Hi-Ho Cherry-O

- Utilize a script that can provide the child with language to use during the game as well as a reminder of the rules. For example, “I got _____ (1, 2, 3, 4) so I can pick _____ (1, 2, 3, 4) cherry(ies).”

- “I got the _____ (dog/bird). Put back 2 cherries”.

- To encourage addition and subtraction skills, provide a number line from 1-10.

CARD GAMES

This classic childhood game can be very abstract and confusing for children with autism. Not only does this game require that children be familiar with the concept of fishing, but also that they utilize language (“Do you have any 5s?”), memory (I need a 5 to make a match, I remember Jane asked for a 5 so Jane might be a good person to ask), and perspective-taking skills (Jane asked Anthony for a 5 so Jane probably has a 5), that can be difficult for a child with autism. In order to make this game more concrete, some adaptations can be made:

Go Fish Adaptations:

- Begin by explaining the concept of fishing and how it applies to the card game being played. An explanation that may work could be that the cards in the pile are like fish in a pond, and the cards in the players’ hands are like fish on a fishing pole. The idea is to get all of the fish from the pond onto the players’ poles, and the winner is the person with the most matches.

- If playing with a 52-card pack, or even if playing with a Go Fish-specific deck, limit the number of cards being used so there aren’t as many cards to handle.

- Play with cards facing up so that everyone can see the cards the other players have, allowing the child with autism to focus less on perspective taking and more on using the appropriate language for the game and understanding how the game is played. (This strategy can be phased out as the child becomes more familiar with the game).

- If cards are hidden from all players, give the child with autism (and the other players if desired), a pencil and paper so they can write down notes (e.g. Jane has a 5) throughout game play to aid with memory. Again, this allows for more focus on game play and having fun, rather than remembering which player has which cards.

Old Maid does not require the same language, memory, or perspective-taking skills as other card games, so it can be a good game for children for whom these skills are a challenge. As the objective of the game is fairly simple: don’t end up with the Old Maid, this game can provide children with autism a good opportunity to practice their social skills with peers throughout game play.

Adaptations for Old Maid:

- If playing with a 52-card pack, or even if playing with an Old Maid-specific deck, limit the number of cards being used so there aren’t as many cards to physically handle.

- Use a cardholder so that children can focus on playing the game and not trying to keep all the cards in their hands at once.

- Provide a script to help children know what to say throughout game play, with phrases such as, “Would you like to play/can I play?” “Your turn!” “I got a match!” “Good game!” “Oh darn, I have the Old Maid!” etc.

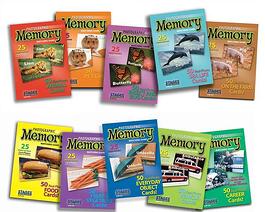

As the name suggests, the game of Memory relies heavily on visual memory, which for some children with autism is a great strength. Other children will struggle, as spatial awareness and understanding the location of items as they relate to each other can be particularly challenging, let alone remembering an item’s location when it can’t directly be seen. In order to support children for whom visual memory is difficult, the following adaptations can be made:

Adaptations for Memory:

- When first introducing the game, use only four cards (two matches), and gradually increasing the numbers of pairs as the child becomes familiar with the game.

- Start with cards facing up in order for the child to practice making pairs and seeing cards in relation to one another. As they become more adept at this, turn some cards over so they can begin to focus on remembering where the pictures are, even when they can’t be seen.

- Use a specialized deck of cards to play the game using a favorite subject, such as animals, pets, bugs and insects, etc.

- War

To play this classic card game, players need an understanding of the number concepts greater than and less than. To aid children with autism or others who might not have these concepts solidified, some adaptations can be made:

War Adaptations:

- If using a 52-card deck, take out the face value cards (Jack, Queen, King, Ace) so that the players don’t have to remember the values of these cards and how they compare to the number cards.

- Provide a number line with numbers from 2 – 10 to assist in determining which number is bigger.

- When the child is ready, add the face value cards back to the deck and add them to the number line in appropriate sequence.

18816 Ventura Blvd.

Tarzana, CA 91356

Phone: 818-996-6620